Ownership: who owns what, and what does that mean?

A few examples to illustrate how ownership plays out in practice.

The municipality rarely owns a substantial share of the real estate in a neighborhood. The majority is in the hands of private homeowners, housing corporations, and other property owners. If the municipality seeks to implement major changes – whether to improve aesthetic quality, introduce a different housing program, or advance sustainability- it must collaborate and/or negotiate or, when necessary, use its formal instruments, such as subsidies and regulations.

The municipality is the formal owner of public space, but residents and visitors can be seen as co-owners in terms of use, maintenance, and social significance.

Schools often have complex ownership structures: the municipality may develop and own the building, while the school board is responsible for managing the facility and the education. These roles do not always align, and tensions can arise between what makes sense from a development perspective.

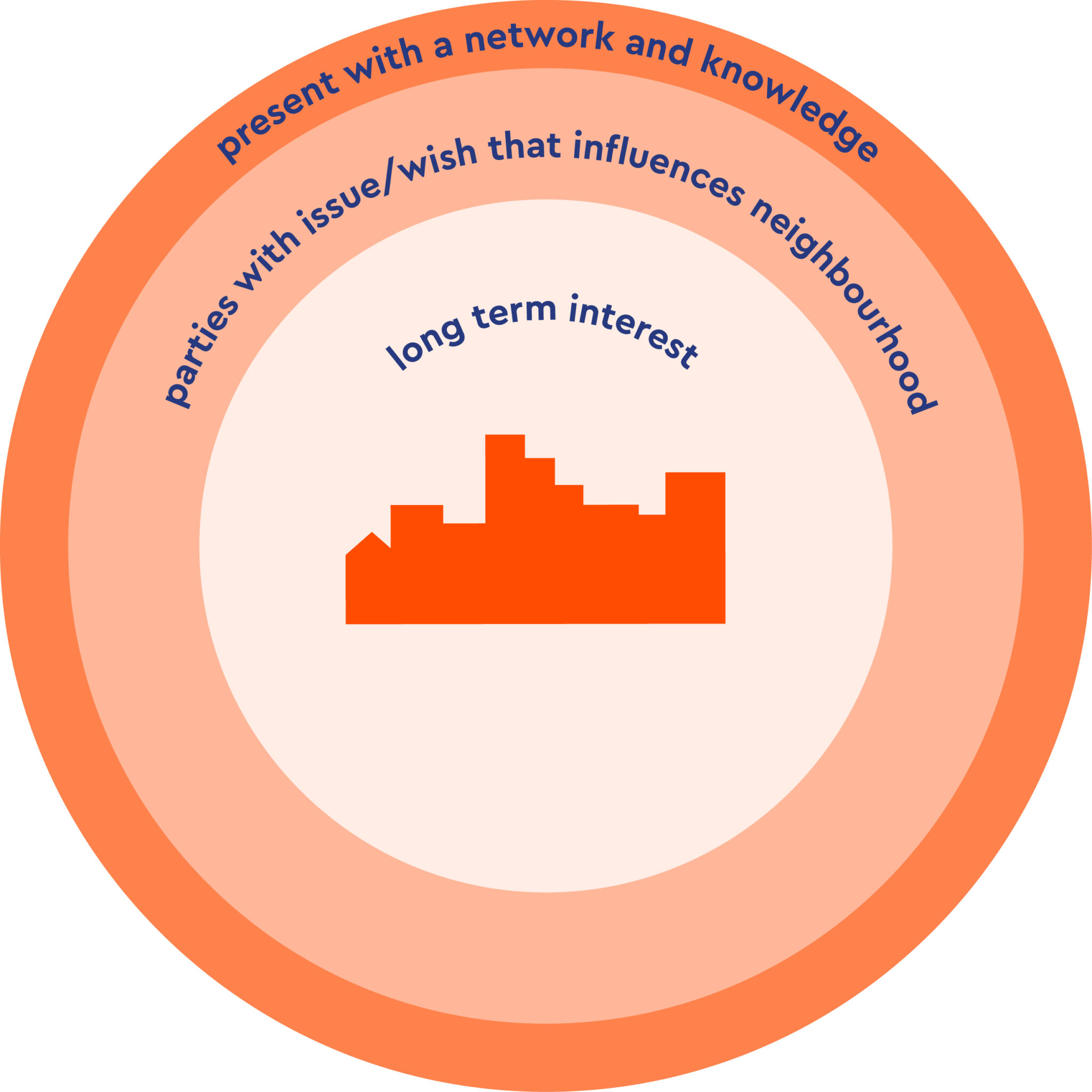

The question is always: how much does ownership weigh on the neighborhood task and how decisive is that? An entrepreneur with a single building is not decisive. But a business investment zone with dozens of local entrepreneurs? That is a potential key player.

Responsibility: ownership is not everything

Responsibility may appear similar to ownership, but the two are not the same. Take, for example, a corporation with a large real estate portfolio in a neighborhood that is in need of renovation. The corporation not only owns the homes but also has a social responsibility to provide good housing for low-income households. In quite a few regeneration neighborhoods, the quality and appearance of homes is a point of concern. Precisely because the quality of housing lays such a foundation for quality of life, the corporation, because of its responsibility, belongs at the core.

Many corporations also feel a social responsibility, probably because of their history. But a responsibility ‘behind the front door’ is not assigned to a corporation. If the corporation does take on that responsibility, it creates friction.

So, the broader the responsibility in the neighborhood, the more firmly you are at the core of the constellation. And at the same time, you cannot sit at the table with an improper responsibility.

Power: formal and informal

The next question concerns the power to make decisions that have significant consequences for others, even in the face of disagreement. In its role under public law, the municipality clearly holds such formal power. Social housing organizations, too, can decide on housing plans that tenants, and also the municipality, may oppose. When formal decision-making power is combined with substantial ownership and responsibility, it becomes highly desirable to have such actors at the heart of a neighborhood renewal board.

At the same time, residents possess considerable informal power. This is often described in negative terms: when residents strongly oppose formal decisions, they can and will make their voices heard, for example through the media or the municipal council. Viewed more positively however, resident’s greatest informal power lies in what they themselves do within the neighborhood: their own activities and organizations. At times, these citizen-led initiatives complement the work of housing corporations or municipalities. At other times, they effectively take over their roles. In either case, the resulting social value exceeds what formal organizations alone can deliver, making this form of power indispensable. For those who hold formal authority, this is a compelling reason to ensure residents have a seat at the boardroom table (a point we will return to later).

Investment scope: those who pay have a say

Investment capacity is a key factor in determining who belongs in the core coalition. Consider, for example, a philanthropic foundation willing to make a substantial investment in a neighborhood park, or a cultural institution willing to plan large-scale, high-impact developments. Both should be seated at the boardroom table, where discussions can ensure that their investments also advance the broader goals of neighborhood renewal.

The municipality is rarely absent from this consideration, provided it is genuinely creating room for investment. Municipal funding is a double-edged sword: it represents valuation of the neighborhood, and it also strengthens the municipality’s negotiating position. By choosing to invest, the municipality gains leverage to encourage, or even require, other parties in the area to invest as well..

Capacity, time, and organization

Neighborhood renewal demands time, beyond day-to-day responsibilities. The question, then, is who considers the renewal important enough to make that time available. The underlying principle is straightforward: those who do the work have a say. In other words, demonstrated commitment is a valid basis for participation in decision-making. Provided that commitment is directed towards the well-being of the neighborhood rather than the pursuit of a personal agenda. For highly organizes actors, such commitment largely comes down to prioritizing capacity.

The situation is different for those without formal organizational structures. Small shopkeepers for example, fall into this category, as do many residents. Have them taking a seat at the table requires organizational support, as well as compensation for the time invested. In this regard, the municipality is the obvious party to provide facilitation, acting in the general interest.

Expertise

Expertise is required from the disciplines relevant to the issues at hand. Whether that is shopping street management, housing programming, or citizen collectives. It goes without saying that parties who possess expertise in-house (or for whom it is logical to connect external expertise to their organization) should also have a voice at the board.

Dependencies

When determining a party’s position within the constellation, it is important to consider how independently that party can act and make decisions. A school, for instance, can be dependent on the municipality’s real estate department for its building. And the welfare organization is 99% shaped by tenders issued by the municipality’s social services department. If you then weigh up who should steer the neighborhood renewal, in the case of the examples, it may be more effective to seat the aldermen responsible for real estate and for social affairs at the table, because ultimately, they are pulling the strings.

The whole neighborhood or a single area

In practice, it often becomes clear that not everyone can be mobilized around the renewal of the neighborhood as a whole. Actors who operate only in a single area and whose contributions primarily affect that area, may be better served by sitting at the table with others who are likewise focused on that area.

In this way, ‘single area tables’ might be operating alongside more overarching governance structures.

Leadership: who is driving the renewal?

Neighborhood renewal requires champions: visible individuals with both the willingness and ability to stand up for the broader interests of the neighborhood. Without such leadership, any constellation remains fragile. Along the way, there will be difficult challenges, complex trade-offs between competing interests, moments when genuinely innovative approaches are required, and situations in which final decisions demand clear accountability. All these moments call for leadership. When such leadership emerges from unexpected parties, that can be a compelling reason to bring those parties into the core of the constellation.

Two parties with a distinct status: municipality and residents

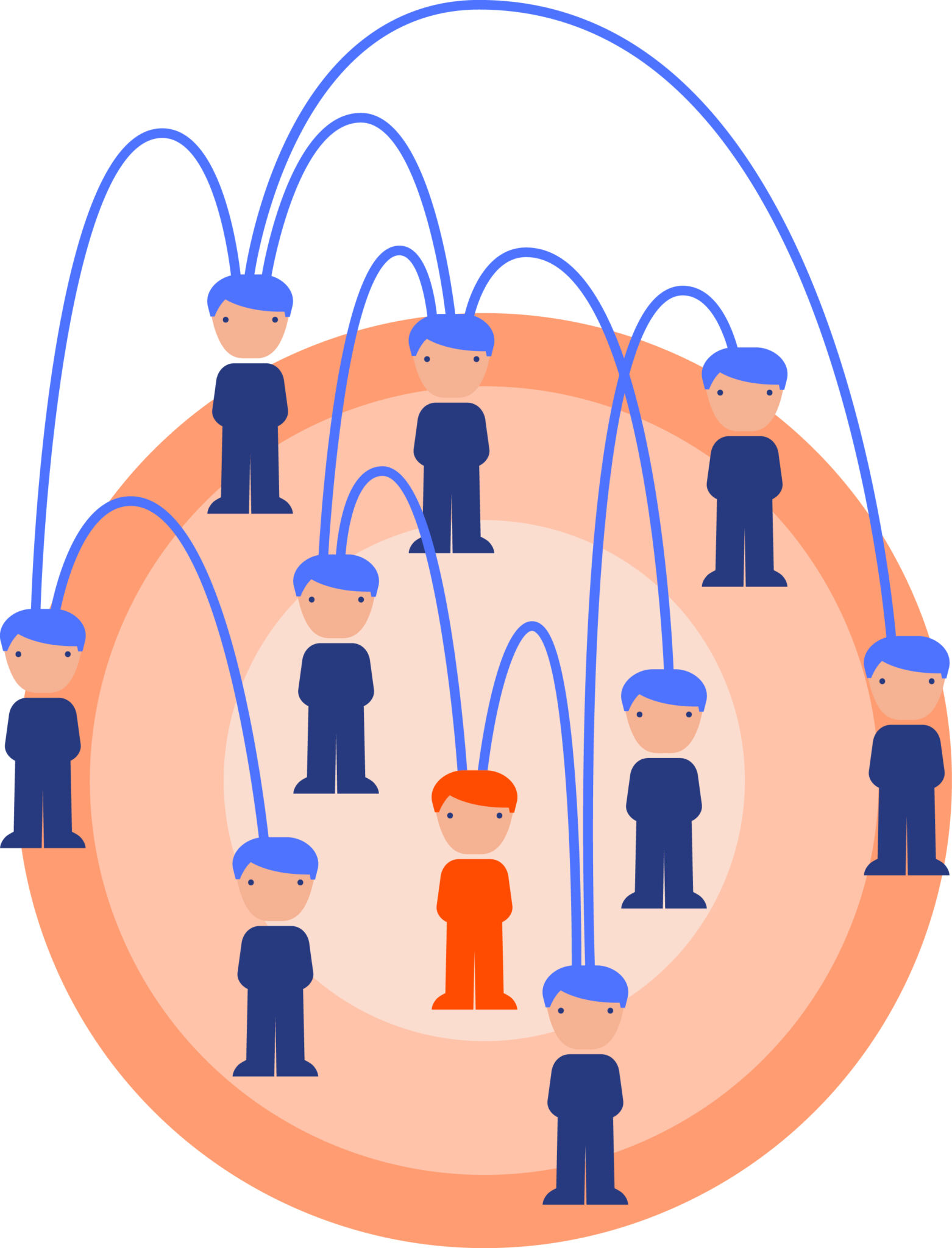

When considering who should occupy which position within the constellation, it makes sense, regardless of the criteria discussed above, to discuss two parties separately: the municipality and the residents.

The municipality holds a distinct status within such a constellation. Despite all arguments in favor of market forces, it remains the actor to which everyone ultimately turns when a neighborhood gets stuck. It alone serves the public interest in a comprehensive sense, no one else does. For that reason, the municipality must play a central and leading role. And yes, the municipality is often multi-headed, internally fragmented, and non-consistent. This reality must be acknowledged and actively managed. Other parties in a coalition, provided they have sufficient leadership, can play a role by exerting pressure on the municipality to ensure that municipal departments work together and remain aligned over time.

Residents have an equally distinctive role. From a neoliberal perspective, they are primarily viewed as consumers, but this framing does not do justice to their significance. Professionals come and go; residents were there before and will remain long after renewal ends. They are involved by definition. Yet, residents are often not organized in ways that professionals readily recognize. Professionals start participation -with the best of intentions- to get residents to come to them. The reverse makes more far more sense: professionals should go to the residents, where they are. Have the agenda and process set together. And make a deliberate choice to sit at the same table, as full participants in governance, with appropriate compensation for the residents. This obviously requires careful consideration of representativeness. More importantly, it requires the municipality and other institutional organizations to incorporate the residents’ voice at the table into their internal processes in a meaningful way. Only then does participation move beyond using residents for consultation and as a sounding board only.

Constellation in neighborhoods A and B

The earlier sections outlined the weighting process and possible positions of actors involved. To conclude, I will sketch two example constellations to bring the outcome to life.

Neighborhood A is characterized by high levels of intergenerational poverty, low literacy, and a striking number of young people who are unemployed at an early age. At the same time, there is a mandate to renovate ten large social housing apartment blocks in the area. In this context, I would invite an alderman for education, an alderman for social affairs, and a representation of young people from the neighborhood to form the core table. Young people are precisely the group you want to create opportunities for in the future neighborhood, so they should be the starting point. Such a table brings together those who hold formal power with those who hold ownership.

In addition, I would invite the welfare organization and a secondary school to a participate in a roundtable in the role of a robust advisory board. At a separate roundtable, I would bring together the parents from the apartment buildings with the social housing organization, and ideally also with the municipality if it intends to address the public space in parallel. The director’s role is to set the agenda for these tables, coordinating their pace, and identify key moments when the tables come together to shape the integrated character of plan.

In neighborhood B, there is a high vacancy rate in the shopping street, affecting both office and retail properties; the shopping street will not cease to exist, but it will contract. There is no retailers’ association in place, and the ownership of retail property is fragmented across multiple owners. At the same time, there is a stagnation in housing mobility, leaving both older and younger residents without suitable housing.

The first step here, is a discussion at an existing table: the council table. The aldermen for economy and for housing will have to join forces to free up resources to turn the tide in the neighborhood. Next, investing in the capacity and organizational strength of the local entrepreneurs becomes top priority. Only when entrepreneurs are supported in taking on their share of ownership of the shopping street and assuming responsibility for it, can a serious start be made. After all, the municipality is not the owner and therefore has very limited control.

If part of the shopping area clearly has potential, then a round table with the municipality, the (newly formed) retailers’ association, and property owners could start steering that part. If another part is particularly suitable for transformation into housing, the municipality could initiate consultations with current property owners and prospective developers to facilitate a breakthrough, by enabling transformation and steering towards the desired housing mix.

Future residents too, could also be given a position in the governance structure by creating a roundtable between developers, the municipality, and these prospective residents to define the contours of the desired housing. This could also take the shape of a cooperative that takes on co-ownership at an early stage and thus helps steer the development process.

Neighborhood B is also very well suited to a constellation based on the principles of a community land trust, in which all involved parties establish a foundation dedicated to a shared goal for the neighborhood, accompanied by an association of all stakeholders to manage that foundation over the long term.

These two completely different examples illustrate what the outcome of the weighting process can look like in relation to specific themes in a neighborhood. The weighting provides guidance, the themes in the neighborhood help point the way. From here, the task is to carefully assemble the puzzle, continually track shifts within the constellation, and tend to the whole with consistent care.