The story of neighborhood X, today

Neighborhood X has around 4,000 residents, of whom around 1,500 have lived there for a long time. The others have lived there for a shorter period and often leave again quickly. There are considerable differences in income, but around 60% of households are on low incomes. Some of them have multiple problems, which appear to be entirely related to the fragile house of cards of temporary employment contracts mentioned earlier. Long-term neighborhood research shows that a large proportion of residents are unhappy with the neighborhood.

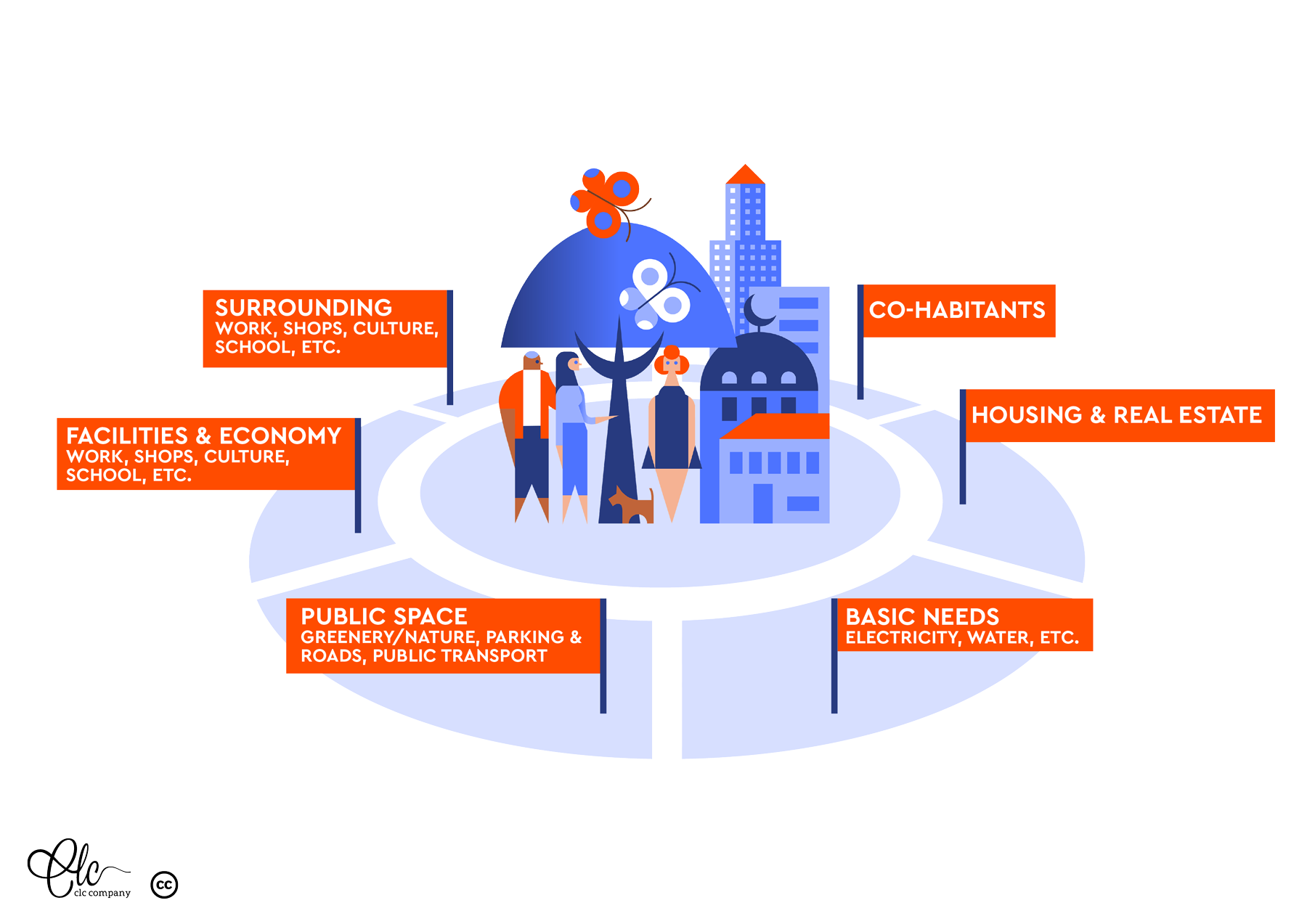

The neighborhood consists of different neighborhoods with very different characters, with little connection between them. A busy, stony thoroughfare literally cuts the neighborhood in half and separates the central park from the shopping street. On paper, the neighborhood has a lot of green space, but in practice, the quality is often mediocre and therefore hardly noticeable. Some neighborhoods have outdated, often problematic homes with a gloomy appearance. And there are parked cars everywhere.

There are many family homes, while the number of single- and two-person households is increasing. Both in the neighborhood and in the surrounding areas, there is a dire shortage of affordable housing. There is virtually no room in the neighborhood for newcomers and people who need some care.

The neighborhood functions primarily as a place to live: most people work elsewhere. There are the necessary shops, but apart from that there is little to encourage socializing or meeting people. This is particularly noticeable for young people: there is little to do on the streets. There are, however, some good sports facilities. There are also several churches, which have managed to build a strong bond with local residents.

The social transitions described above are clearly noticeable in neighborhood X and represent a current challenge.

The story of neighborhood X, later on

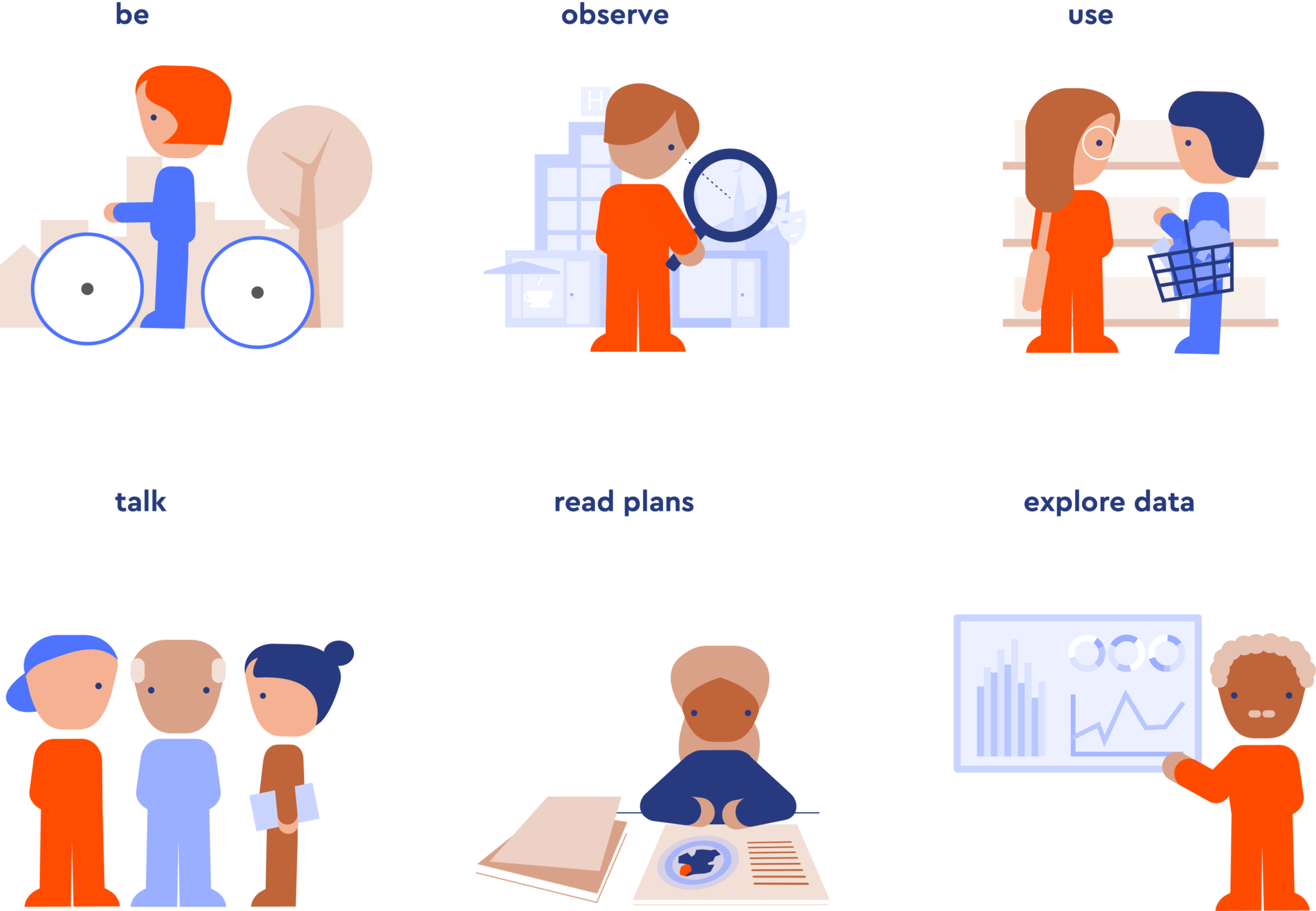

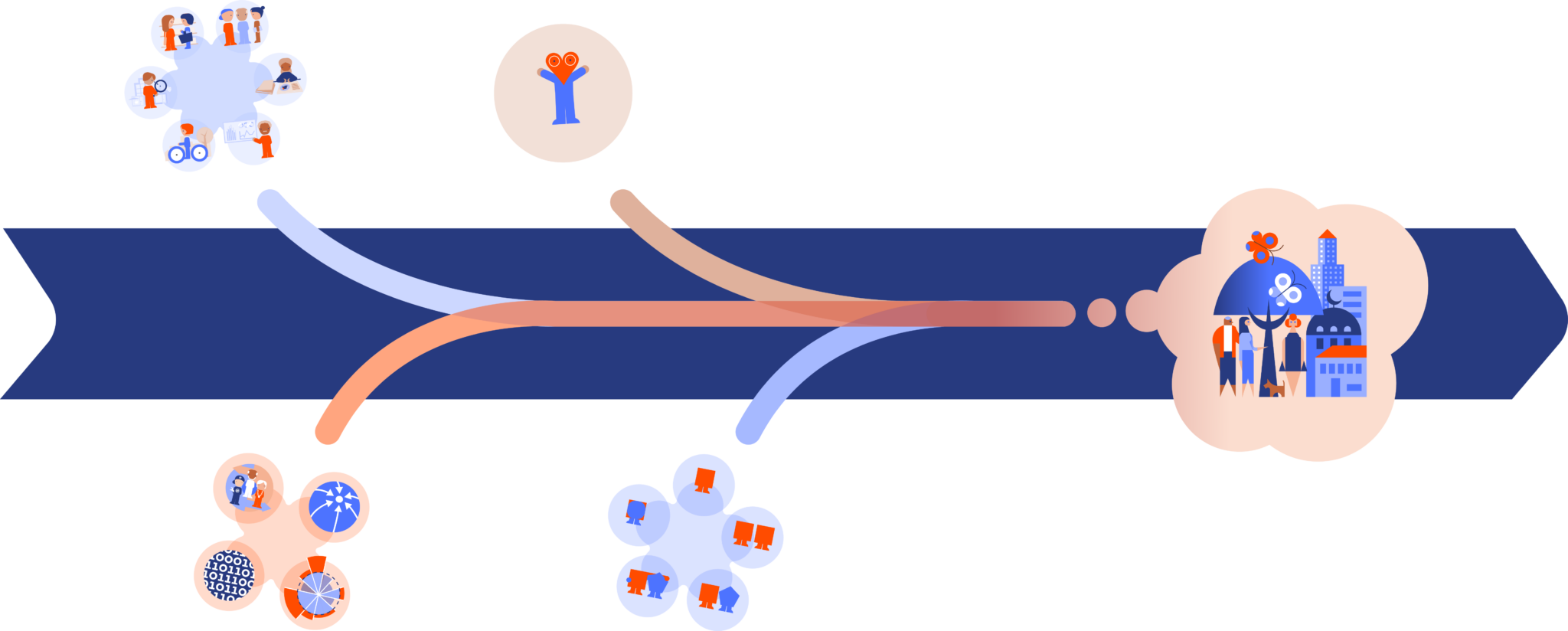

More and more diverse people are staying in the neighborhood longer, indicating their appreciation for it. This is the result of coherent measures: a better urban design, a more diverse housing supply, and more room for personal initiative, all aimed at reducing alienation and increasing connectedness.

The main road has been transformed into a green boulevard and car mobility has been reduced by creating parking hubs on the outskirts instead of parking in the streets. Neighborhoods with many monotonous, unattractive homes have been renovated with attention to the use of materials and variety in appearance. Separate green spaces have been connected to form a green route that runs through the entire neighborhood; this is used by sports facilities and individual residents for sports and walking.

The park and shopping street together form the bustling heart of the neighborhood, as the shopkeepers work together in an organization to organize regular events. The park also has an affordable coffee stand with activities, run by a residents’ cooperative that involves schools, churches, and a retirement home in its programming. The cooperative also plays an active role in maintaining the green spaces in the neighborhood.

The housing stock has been renewed: renovation, the addition of new homes, and a few demolition/new construction projects have led to the preservation of the number of social housing units, but also to more affordable, smaller homes for single-person households. Two locations for cooperative living have been realized, which also organize activities for the neighborhood.

With government support, young people have set up a youth hub with a lively social media account that they manage and program entirely themselves. They have set up a neighborhood business that offers odd jobs in the neighborhood at an affordable rate, both for repairs and for assistance with digital questions.

Every week, a mobile coffee stand drives through the neighborhood, staffed by social workers who provide comprehensive support on a range of issues, from healthcare and taxes to employment, digital skills, and just a friendly chat.

Some guiding principles for the implementation of the renewal of neighborhood X

>Meeting people is central to all housing and public space projects, alongside ensuring privacy.

>The municipality actively facilitates residents and entrepreneurs: it makes money available (and encourages its use) for various initiatives in the neighborhood and also supports these if regulations get in the way. There is a conscious effort to encourage young people to develop something themselves, to get residents involved in setting up activities in the park, and to get shopkeepers to work together. Neither the municipality nor any welfare organization ever takes over any of these initiatives.

>Assistance for people who need it is provided in a neutral, accessible manner (people do not have to go to a service desk), and social workers have the mandate to arrange everything for residents.

>Demolition/new construction is only carried out in carefully considered locations in order to add more small homes.

>The visual quality of homes to be renovated must meet certain requirements (not just the interior), and the municipality monitors this.

>Sustainability is an integral part of the renewal agenda and is explicitly included in the implementation choices for all projects.

>Green spaces will be given greater recreational value – every intervention in public spaces will include a little extra to improve the quality and attractiveness of the green spaces.