And then, one day, the moment arises when the neighborhood calls for a thorough renewal. Not just replacing a few streetlights, appointing a new community center manager, or launching a new housing project. What’s needed is a comprehensive future plan that combines physical, economic, and/or social interventions.

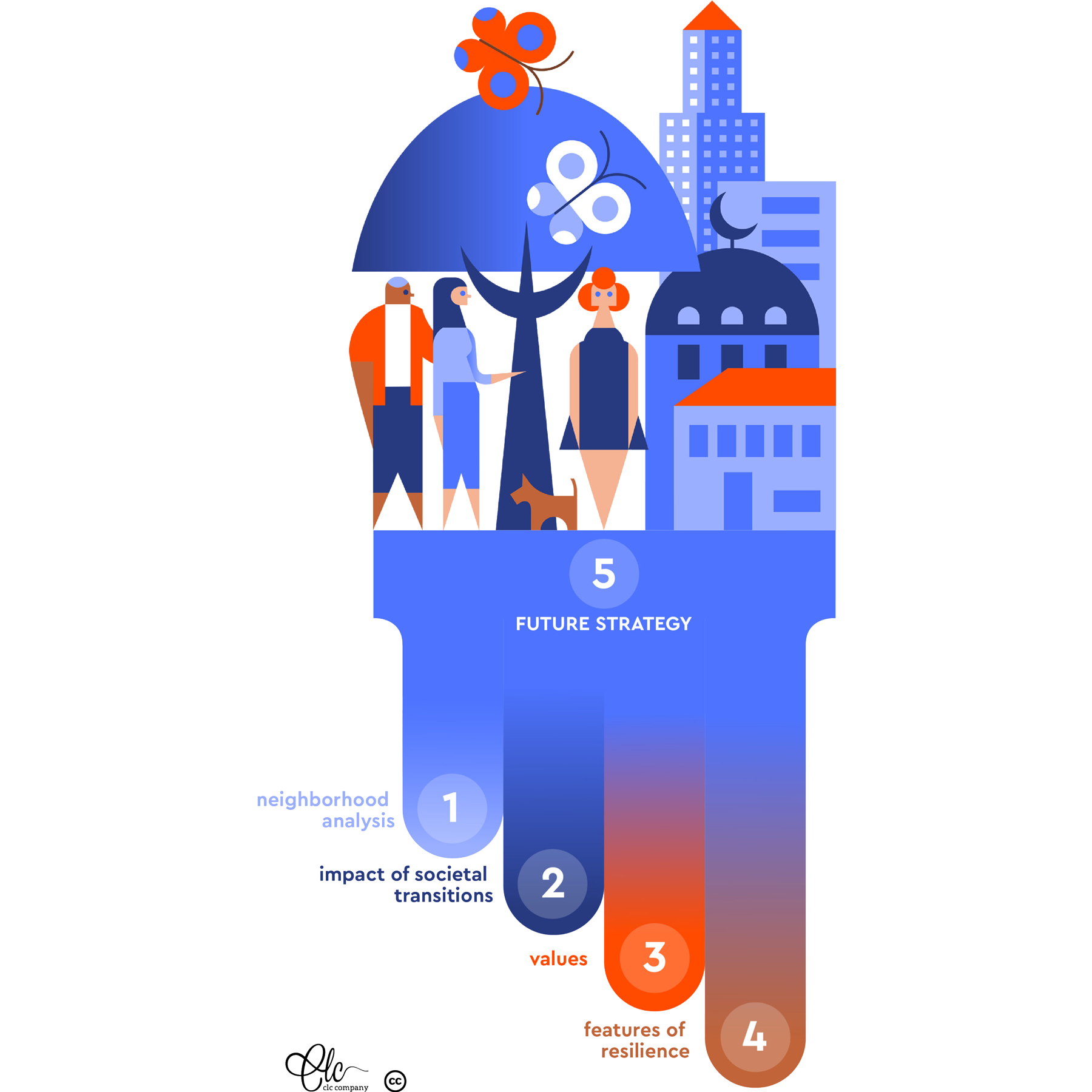

You’re about to make significant investments. How can the neighborhood be renewed in a future-proof way? How do you build resilience within the neighborhood? How do you work towards a happy neighborhood? I take you on a journey through the strategizing process, touching upon:

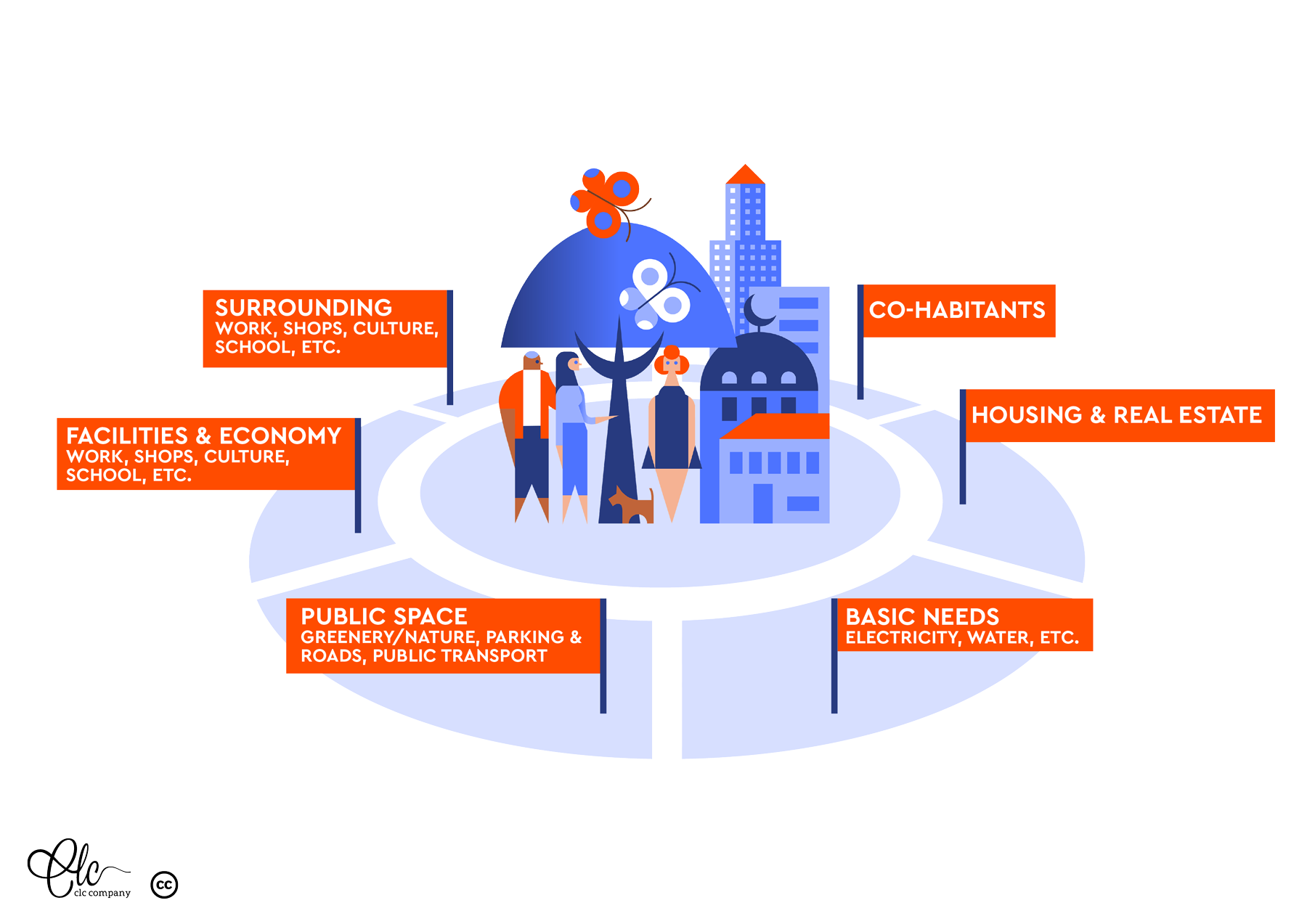

Systemic perspective on the neighborhood,

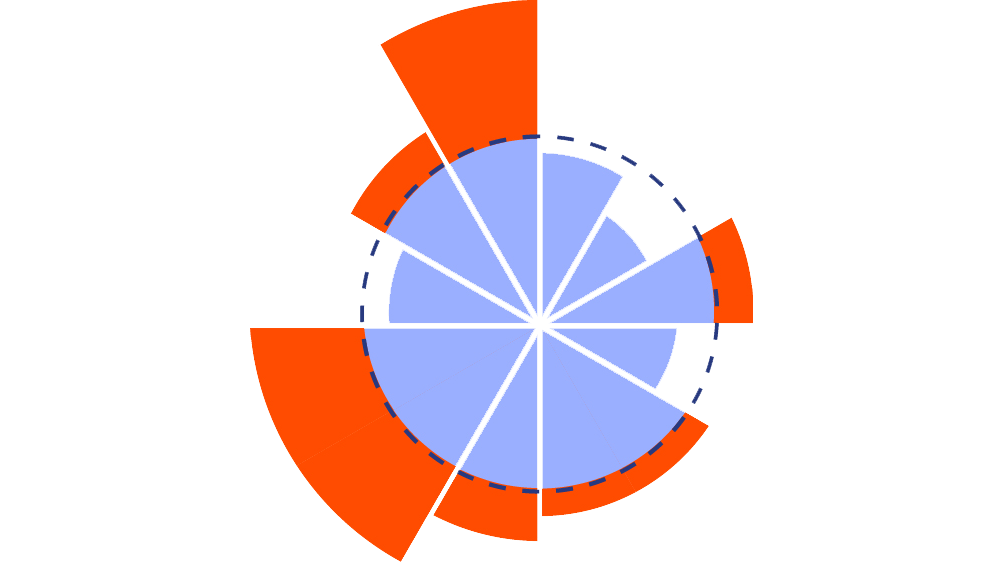

Deep dive analysis method,

Impact of societal transitions,

Clear view on resilience,

Transdisciplinary work, and

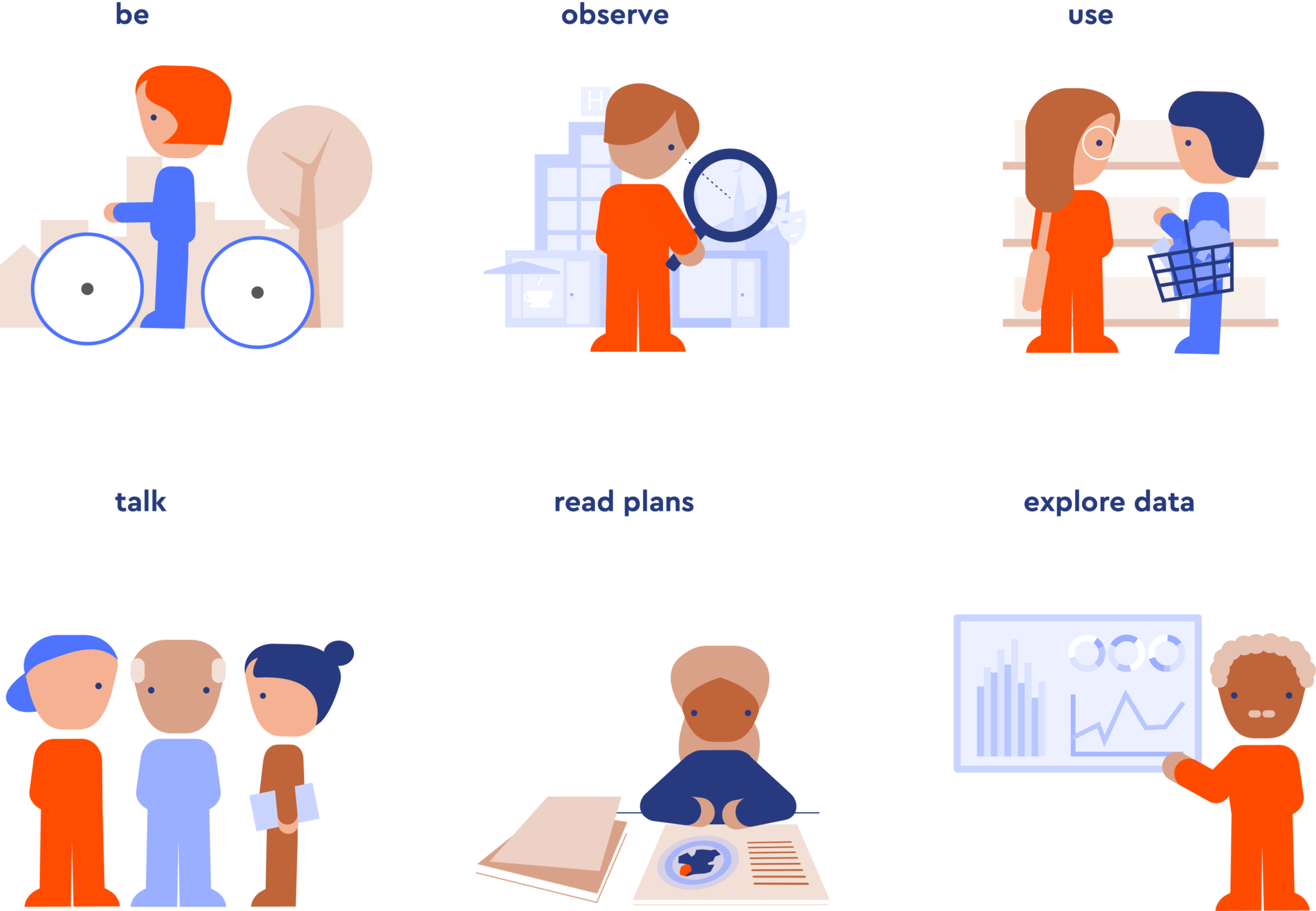

Working from a position of empathy and wonder, for the neighborhood and the people.This long read offers you a methodology.

But these are the neighborhoods we have created together, and that also gives us the responsibility to renew them. So it’s up to us to rise to the challenge of managing that complexity. And in this area, there is surprisingly little guidance from the academic world. Based on my experience, intuition, and knowledge, I’ve developed a methodology to tackle this complexity. In this long read, I offer a step-by-step plan to create an integrated strategy or future plan.

My goal is to generate more dialogue about neighborhood transitions, to make us more aware of the choices we make, and to become better—together—at renewing neighborhoods. So this long read is also an invitation for feedback and conversation.

Let me propose a structure to move through the strategy process of creating a future plan for a neighborhood, which is also the structure for this article. I have experienced that it makes sense to walk through five distinctive steps to reach a comprehensive strategy. First is obviously to analyze the current situation in the neighborhood by a thorough assessment. Next is to take a step back and also analyze how societal transitions impact the neighborhood, both now and in the emerging future. Third is to establish the fundamental values that guide your vision, because strategizing a neighborhood’s future is also based on personal, professional and societal values.